Hunger and malnutrition: the key datasets you need to know

How much food is available? What are people eating? How much do poor people spend on food? We explore the statistics

A woman sells skinned papaya in a market in Lagos, Nigeria, October 2012. Photograph: Sunday Alamba/AP

More than 100 UK development NGOs and faith groups have launched amega-campaign to lobby the G8 on actions they say will be key to ending global hunger. Their list of demands is long and ambitious, covering more aid, efforts to tackle tax dodging, land "grabs", and the lack of transparency around investments in developing countries.

Hunger and food security are emotive issues, but hard to capture with the single "killer" statistic often favoured by high-profile campaigns. The UN, which has long produced estimates of global hunger, has reworked its figures and is backing away from single statistics. In October, the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) released a suite of more than 20 indicators, available for most countries, which it said could offer a more rounded picture of the causes and consequences of food insecurity.

How much food is available? What are people eating? How much do poor people spend on food compared with other items? How are children affected by food insecurity? These are some of the issues covered. The FAO plans to run a global poll to monitor food insecurity based on peoples' experiences, to better understand the challenges communities face in accessing food.

We've pulled out some of the key figures, and you can download the full set below. What can you do with the data? Which indicators do you think are the most revealing?

Global hunger: the big picture estimates

According to the UN's new hunger figures, the millennium development goal (MDG) to halve the prevalence of hunger by 2015 is within reach. The new estimates, which draw on updated data and a revised methodology, suggest the percentage of hungry people in developing countries has fallen from more than 23% in 1990-92 to less than 15% in 2010-12, or around 850 million people.

There are important caveats, however. Progress since 2007 appears significantly slower, and there are stark variations between regions.

And there would still be hundreds of millions of hungry people in the world even if the MDG target is met.

Food prices

The UN hunger indicator's inability to capture the impact of short-term price spikes and other economic shocks (unless they fundamentally change long-term consumption patterns) is seen by some as a key shortcoming. A local food price index, which estimates affordability, and an indicator tracking volatility in domestic prices, seen as a key measure of future food insecurity, are among the statistics released last year.

A further indicator looks at how much the poorest 20% of households are spending on food compared with other items.

When prices go up, people will often sacrifice other household spending rather than go without food. Using data from household expenditure surveys, this indicator aims to capture the economic consequences of rising food prices.

How are people affected by food insecurity?

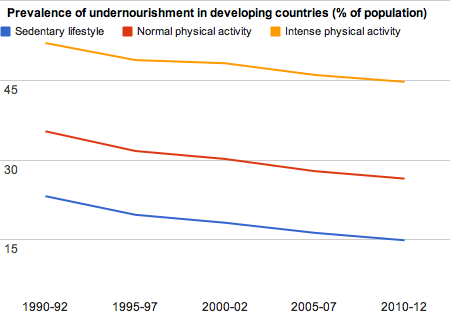

A key criticism of the UN hunger indicator is that it sets the threshold too low, using the minimum calories needed for a "sedentary lifestyle". The number of hungry people today could be as high as 1.5 billion (or more than 25% of the world's total), if the threshold was instead set as the minimum needed for "normal activity", or nearly 2.6 billion (nearly 45%) for "intense activity".

The percentage of children under five who are stunted, underweight, or affected by wasting (measured as low weight for height) are other key indicators of how food insecurity affects long-term human development. The UN's proposed suite of food security indicators also tracks these impacts, along with the percentage of adults who are underweight.

The 'double burden' of undernutrition and obesity

As incomes rise, diets are becoming more diverse around the world. This has given rise to a "double burden" in some developing countries, where undernourishment co-exists alongside rising levels of obesity.

Globally, obesity has more than doubled since 1980, with the number of overweight adults now estimated at 1.4 billion. "The world is increasingly faced with a double burden of malnutrition, whereby undernutrition, especially among children, co-exists with overweight and diet-related chronic diseases and micronutrient malnutrition," the UN's 2012 State of Food Insecurity in the World report said. "Being overweight is not necessarily a matter of eating too much food, but eating food that is not nutritious, and poor consumers may have less education and access to information about nutrition. Another part of the explanation may be the rapidly growing supply of previously unavailable products (eg some processed foods, soft drinks and snacks) in the modern retail chains of many developing countries. In many cases, such products replace traditional foods, including street foods in urban areas."

Download the data

More data

World government data

Development and aid data

Can you do something with this data?

• Flickr Please post your visualisations and mash-ups on our Flickr group

• Contact us at data@guardian.co.uk

No comments:

Post a Comment